Gradually, and then suddenly.

Inexorable, arithmetical, consequence of steady growth:

the Hemingway Decline

Biodiversity loss is complex to measure, but the evidence of a crisis is now overwhelming. (Here's a good summary from the Grantham Research Institute at the LSE.) Declines of 70%, 80%, 99% in the populations of various lifeforms which not only deserve to exist in their own right, but are essential to the future of humankind too... the numbers are terrifying.

The speed of these declines seems faster than our collective ability to respond. It's 50 years since the publication of 'Limits to Growth', and too many policymakers still assume GDP growth as an appropriate target - an assumption that should be called out in every discussion and forum!¹ Forming new approaches will be more challenging, but much more interesting. It's encouraging to see interdisciplinary groups brainstorming practical policy options for 'prosperity with reduced use of materials and energy', and, at last, alternative goals and KPI emerging from Wellbeing Economy Governments.

Mental models are important - and often made up of smaller building blocks - mental modules. Evocative words and phrases help, and our language evolves. Biodiversity entered discussion in 1985; planetary boundaries in 2009; the Wood Wide Web by 2016. Market fundamentalism c.1991; doughnut economics in 2012; externality-denying capitalism c.2021.

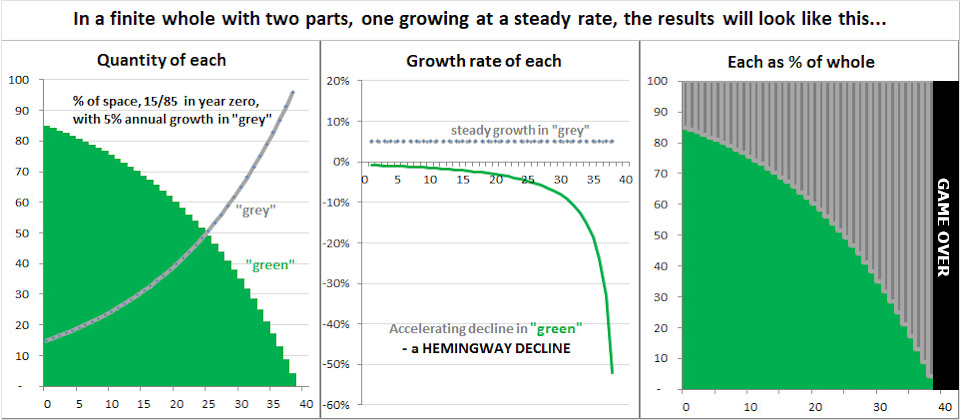

Arithmetical models are equally important. Compound growth is key to the enrichment of investors and the impoverishment of debtors, so effort is devoted to explaining the power of compounding. (Unfortunately there is some doubt as to the comprehension level of our leaders, as shown in the popularity of the pandemic cartoon on exponential growth by Jens von Bergmann.) I have seen little attention to compound growth's consequence, which Guy Thomas and I call the Hemingway Decline. In a finite space, divided into two mutually exclusive parts, a steady rate of growth in one will result in not just steady decline, but an accelerating rate of decline in the other.

This is just arithmetic - an abstraction. (Thanks to Guy Thomas for setting out the formal mathematical language in his complementary 2019 article 'Two parts of a whole: compound growth and Hemingway decline'.) It is however worth shifting perspective, to understand and experience the accelerating decline of the dwindling part, rather than focusing only on growth situations (or on how to restart them). Please check the calculations yourself, either with the formulae, or experimentally; you may, like us, find the results disconcerting.

The Hemingway Decline may be relevant in many circumstances. Consider a working person who spends x% of his time on bureaucracy, which expands at y% a year, and the time remaining for useful work... or alternatively, consider the expansion of weeds in a flowerbed. In the real world, growth will sometimes slow as it approaches limits - but not always! Sometimes it will continue relentlessly until the counterpart is extinguished.

Those of us whose job is to focus on man-made activities and their growth may be unaccustomed to thinking about the natural world - but we should, as the diminution of nature presents growing risks. There are vital dependencies, many of which we're only just beginning to understand - and meanwhile, there are also still marvels to enjoy.

It was the rapid diminution of nature that first prompted me to make simple calculations, as explained below. Even this very simple two-part model had explanatory value. As with Hemingway's description of bankruptcy, extinction crises may start gradually, and then accelerate. Gradually, and then suddenly - it's a Hemingway Decline.

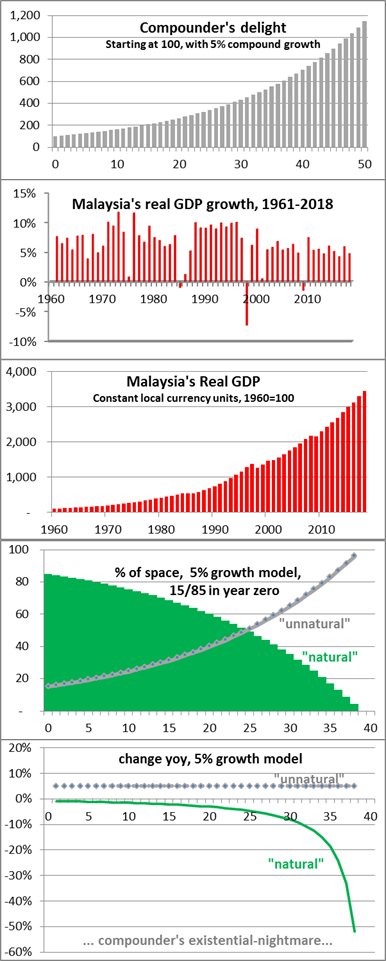

In July 2019 I was reflecting on change in Malaysia, a country which I had first experienced exactly 36 years earlier. Over that period, real GDP had compounded at an annual rate of 5.5% - so over the period, it had grown 7-fold. Since 1960, the size of the economy had multiplied 35 times. This is what I wrote then.

|

An everyday story of Asian growth

Investors in Asia routinely see graphs like the first one on the right. It

could represent the past or the future, the actual or projected march of food

sales, widget manufacture, or passenger throughput. Actually, this particular

chart just represents 5% compound growth over time. 5% may seem a pedestrian

rate to choose: we investors are often looking for the sweet spots at which much

higher rates are achieved by individual industries, and tracking consumption of

shampoo, smartphones, or security services. The whole Chinese economy has grown

at more than 9% per annum for the last fifty years, is still growing at well

over 6%, and it is easy to find individual sectors growing faster - but bear

with me while I focus on the consequences of compound annual growth at this

moderate annual rate of 5%. There are many Asian countries which believe that 5%

is sustainable, with governments that are targetting to maintain their rate of

growth at this level or more. Economic growth remains correlated with the

consumption of ever more materials and Stuff: there are many industries growing

volumes and footprint at this pace.

Compound growth, an investor's best friend?

Naturally I have vivid memories of my first few years in Malaysia, and the

remarkable changes that have occurred. From my first rented home I had wide

views of the Main Range mountains of the Peninsula, not just green but also

strikingly blue. The streets were shaded by the huge canopies of brightly

flowering red and gold rain trees, and everyone lived in houses with gardens: it

was widely agreed that apartment living would never be acceptable in Malaysia.

Weekends were spent on jungle hikes to crystal-clear waterfalls, or occasional

drives to the East Coast, which had hundreds of miles of pristine coastline up

which giant leatherback turtles lumbered majestically. The human population was

14 million, in a land area that for practical purposes seemed infinite. I

marvelled at the huge rainforest trees, at the extraordinary variety of

brightly-coloured 6-inch butterflies, and at the bounteous harvest of a fishing

kelong.

That world has vanished. Some species that I remember may survive in remote places, but they are no longer part of our daily lives. Blue-green views have given way to grey urban dystopia. The dangerous timber lorries are rarely seen now, because large logs of tropical hardwood are mostly a memory. Leatherback turtles are gone, and it is decades since I saw any such butterflies. Friends drove 1.5 hours last weekend to buy fish, supplies being inadequate to reach the city. I mention this to introduce a simple simulation which suggests that my impressions of rapidly accelerating losses and crises may not be distorted by sentiment or nostalgia.

We should be careful what we wish for...

Consider a simple model in which our land area is either "unnatural"

(concreted, polluted, or otherwise altered; devoted to the modern

industrial world and its associated residential and commercial

structures), or "natural" (plant-covered with ecoservices) - a gross

simplification of course, with room for endless debate about

classifications and chemical agriculture.

Suppose that the initial land allocation is 15% to the "unnatural" or

industrial economy, leaving 85% "natural". Assume a steady 5% volume

growth in the former, year in and year out. Charts 4 & 5 show the

outcome. After 36 years, the "unnatural" industrial land area would be

87% of the total, leaving 13% for the natural world. The former would

have expanded by 5.8 times; the latter would have shrunk to 15% of its

initial size. Most striking is the rate of change. As the industrial

economy grows at a steady 5% pa (now taken for granted, to the extent

that any slowdown may be seen as a bad thing, to be countered by

energetic government), the decline in remaining "natural" area

accelerates. For the first fifteen years, the shrinkage is 1 or 2% pa -

barely noticed by most people; what remains is still huge, so little effort is

made to protect it. In year 25, the loss is 5% in a single year, with an 18%

reduction over the previous five years. In year 30, 8% and 29% respectively. In

year 36, 24% and 59%. My last chart, of the change in each period, stops at year

38: I leave you to extrapolate what happens next.

Now, this is just a model. The two inputs are the growth rate, and the initial land allocation to the industrial economy. 5% and 15% are the two figures that first came to mind, thinking about Malaysia when I arrived, as I started to wonder whether the pace of environmental destruction can really have accelerated as much as my impressions suggest. One could play with different figures, considering different definitions / assumptions / areas of focus, but I have not attempted to fine tune this. Different starting points would give different results, but the pattern would be similar: given a finite space, and one activity which crowds out another, the arithmetic of steady growth in the former results in accelerating rates of decline in the latter.

I wonder how widely this is understood. Many of us investors are keenly aware of the power of compound growth, and notice that others may grasp it less well; we tend not to draw attention to the corollary of accelerating decline. We may not think about it so much, because it relates to areas or aspect of life that we experience less, and provide us with few investment or career opportunities. We citydwellers may not see these areas or phenomena regularly, and may fail to understand intricacies and interconnections. We may pay less attention because no monetary values have been ascribed, nor taxation opportunities identified, so there are few statistics, making no regular news, and evidence-based people focus on the quantified. We may however lament the loss of butterflies more than threats to all insects, illogical as that would be, because the former are pretty and the other word evokes creepy-crawlies. (I notice that recent reports on plunging insect populations from National Geographic and Mongabay both lead with butterfly pictures; they deserve to be read.)

I am fortunate to have an office in the city and a house bordering secondary jungle, an interest in both investment and the natural world, and friends in finance as well as zoology and conservation. I am sorry to report an impression of dizzying acceleration in Malaysia's destruction of natural habitat and of ecosystems - and my simplistic arithmetic model suggests that my subjective impressions may not be deluded. Moreover, I spend too little time these days on and under water; like most people, I have more day-to-day experience on land than of what is happening to coastal and ocean habitats, and that may be worse. I believe that we should change our behaviour, on the precautionary principle.

My focus on Malaysia here is because I have the advantage of that 36-year comparison, and can date it accurately because of my own experiences in particular years, rather than because events here are unusual. Sadly, despite great natural beauty and biodiversity, it is not anomalous in the pace of destruction, which is similar or even faster in much of Asia, and throughout the developing world. It seems clear to me that ecosystem destruction undermines the foundations of our societies' current way of life, and that this is no longer the logical-but-distant project that it seemed when I was a student, but a threat that could start to bite seriously any time from now on.

10 Jul 2019, lightly edited from original

Four years on, environmental destruction continues apace in Malaysia. More hills and beaches and seagrass meadows have disappeared. (Seagrass meadows are vital habitat for juvenile fish.) River pollution is problematic. We have more landslides, floods and droughts. Many local food sources are depleted. Remaining options for quarrying are increasingly controversial, and contested. Logging and quarrying is taking place in areas previously designated as forest reserves. It is rumoured that forest reserves are still counted as forest, even if quarried? and certainly oil palm plantations are counted towards forest cover, despite the impoverishment of their soil and the problems arising from chemical use. More and more citizens are alarmed - and many now agree that encouraging construction as a driver of GDP growth did not lead to prosperity. A new government is reassessing priorities, and the central bank is considering nature-based financial risks. Necessary reappraisals have started in Malaysia, as in a growing number of countries around the world. The terrifying arithmetic of the Hemingway Decline shows us the urgency of reflection, and of change.

Claire Barnes, 28 Jan 2023

- One might quote UN Secretary-General António Guterres: "Global well-being is in jeopardy, in large part because we have not kept our promises on the environment... We need to change course - now - and end our senseless and suicidal war against nature... We must place true value on the environment and go beyond Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a measure of human progress and well-being. Let us not forget that when we destroy a forest, we are creating GDP. When we overfish, we are creating GDP. GDP is not a way to measure richness in the present situation in the world. Instead, we must shift to a circular and regenerative economy."