Update, 9 August.

The statistical feature discussed here now has a name, thanks to Guy Thomas

and his helpful article on

'Two parts of a whole...', which sets

out the formulae.

It has also prompted me to correct my title and terminology. An exponential decline would be a constant percentage rate of decline; here I wish to draw attention to accelerating rates of decline, and a simple statistical model of everyday causes. Extinction crises, and the undermining of foundations, may happen gradually, and then suddenly. It's a

Hemingway decline

. . .

Apollo Asia Fund's NAV fell 0.2% in the second quarter, to US$2,126.94.

It was a mercifully quiet quarter for company-specific developments from our portfolio holdings, given everything else coming over the newswires, and the potential for geopolitical realignment and the rewiring of the global economy - so let's take a break from all that, to review part of the standard investment case for Asia, and inherent risks often ignored.

An everyday story of Asian growth

|

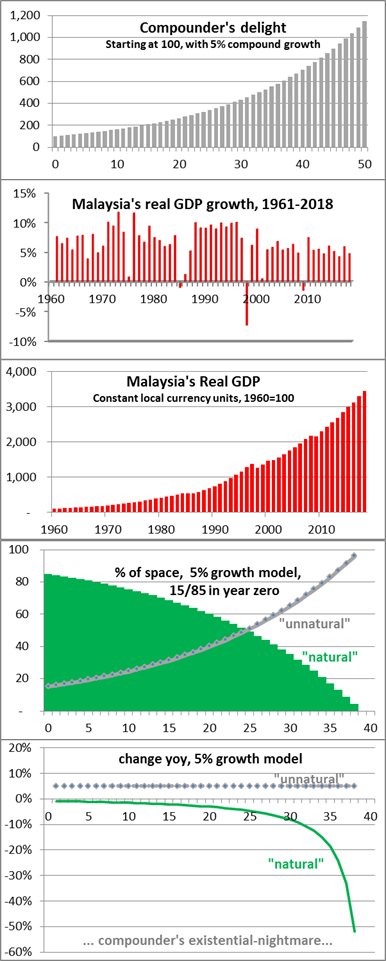

I had the good fortune to be posted to Malaysia in 1983. I arrived on the day after Henley Royal Regatta, which makes it 36 years ago this week. Over that period, statistics tell us that real GDP has compounded at an annual rate of 5.5% - so over the period, it has grown 7-fold. (It has slowed slightly over the decades, but the next two charts show that this period was no aberration: some spectacular recessions now look like mere blips in the upward march, and since 1960 the size of the economy has multiplied 35 times.)

Compound growth, an investor's best friend?

Naturally I have vivid memories of my first few years in Malaysia, and the remarkable changes that have occurred. From my first rented house I had wide views of the Main Range mountains of the Peninsula, not just green but also strikingly blue. The streets were shaded by the huge canopies of brightly flowering red and gold rain trees, and everyone lived in houses with gardens: it was widely agreed that apartment living would never be acceptable in Malaysia. Weekends were spent on jungle hikes to crystal-clear waterfalls, or occasional drives to the East Coast, which had hundreds of miles of pristine coastline up which giant leatherback turtles lumbered majestically. The human population was 14 million, in a land area that for practical purposes seemed infinite. I marvelled at the huge rainforest trees, at the extraordinary variety of brightly-coloured 6-inch butterflies, and at the bounteous harvest of a fishing kelong.

That world has vanished. Some species that I remember may survive in remote places, but they are no longer part of our daily lives. Blue-green views have given way to grey urban dystopia. The dangerous timber lorries are rarely seen now, because large logs of tropical hardwood are mostly a memory. Leatherback turtles are gone, and it is decades since I saw any such butterflies. Friends drove 1.5 hours last weekend to buy fish, supplies being inadequate to reach the city. I mention this to introduce a simple simulation which suggests that my impressions of rapidly accelerating losses and crises may not be distorted by sentiment or nostalgia.

We should be careful what we wish for...

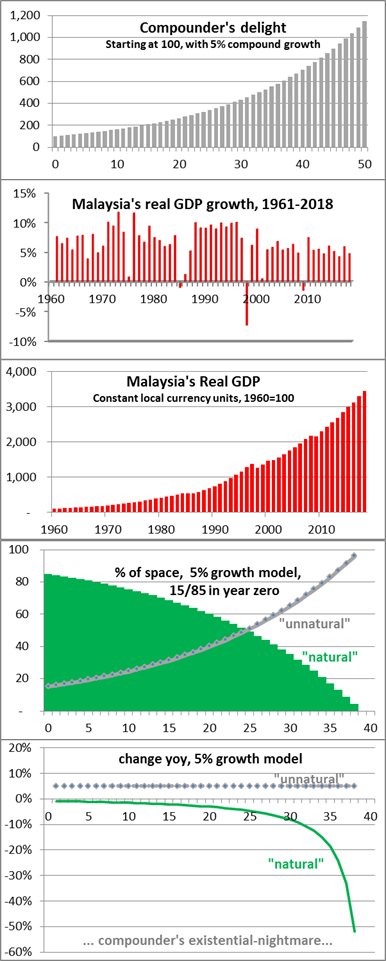

Consider a simple model in which our land area is either "unnatural" (concreted, polluted, or otherwise altered; devoted to the modern industrial world and its associated residential and commercial structures), or "natural" (plant-covered with ecoservices) - a gross simplification of course, with room for endless debate about classifications and chemical agriculture.

Suppose that the initial land allocation is 15% to the "unnatural" or industrial economy, leaving 85% "natural". Assume a steady 5% volume growth in the former, year in and year out. Charts 4 & 5 show the outcome. After 36 years, the "unnatural" industrial land area would be 87% of the total, leaving 13% for the natural world. The former would have expanded by 5.8 times; the latter would have shrunk to 15% of its initial size. Most striking is the rate of change. As the industrial economy grows at a steady 5% pa (now taken for granted, to the extent that any slowdown may be seen as a bad thing, to be countered by energetic government), the decline in remaining "natural" area accelerates. For the first fifteen years, the shrinkage is 1 or 2% pa - barely noticed by most people; what remains is still huge, so little effort is made to protect it. In year 25, the loss is 5% in a single year, with an 18% reduction over the previous five years. In year 30, 8% and 29% respectively. In year 36, 24% and 59%. My last chart, of the change in each period, stops at year 38: I leave you to extrapolate what happens next.

Now, this is just a model. The two inputs are the growth rate, and the initial land allocation to the industrial economy. 5% and 15% are the two figures that first came to mind, thinking about Malaysia when I arrived, as I started to wonder whether the pace of environmental destruction can really have accelerated as much as my impressions suggest. One could play with different figures, considering different definitions / assumptions / areas of focus, but I have not attempted to fine tune this. Different starting points would give different results, but the pattern would be similar: given a finite space, and one activity which crowds out another, the arithmetic of steady growth in the former results in accelerating rates of decline in the latter. I wonder how widely this is understood. Many of us investors are keenly aware of the power of compound growth, and notice that others may grasp it less well; we tend not to draw attention to the corollary of accelerating decline. We may not think about it so much, because it relates to areas or aspects of life that we experience less, and provide us with few investment or career opportunities. We citydwellers may not see these areas or phenomena regularly, and may fail to understand intricacies and interconnections. We may pay less attention because no monetary values have been ascribed, nor taxation opportunities identified, so there are few statistics, making no regular news, and evidence-based people focus on the quantified. We may however lament the loss of butterflies more than threats to all insects, illogical as that would be, because the former are pretty and the other word evokes creepy-crawlies. (I notice that recent reports on plunging insect populations from National Geographic and Mongabay both lead with butterfly pictures; they deserve to be read.)

I am fortunate to have an office in the city and a house bordering secondary jungle, an interest in both investment and the natural world, and friends in finance as well as zoology and conservation. I am sorry to report an impression of dizzying acceleration in Malaysia's destruction of natural habitat and of ecosystems - and my simplistic arithmetic model suggests that my subjective impressions may not be deluded. Moreover, I spend too little time these days on and under water; like most people, I have more day-to-day experience on land than of what is happening to coastal and ocean habitats, and that may be worse. I believe that we should change our behaviour, on the precautionary principle.

Malaysia is not a huge part of our investment portfolio, and I focus on it here because I have the advantage of that 36-year comparison, and many points of observation, rather than because it is unusual. Sadly, despite great natural beauty and biodiversity, it is not anomalous in the pace of destruction, which is similar or even faster in much of the region we cover, and throughout the developing world. It seems clear to me that ecosystem destruction undermines the foundations of our societies' current way of life, and that this is no longer the logical-but-distant project that it seemed when I was a student, but a threat that could start to bite seriously any time from now on.

What might an investor do? (apart from reducing, reusing...¹)

| Geographical

breakdown by listing; 30 Jun 19 |

% of

assets |

| Hong Kong | 22 |

| India | 2 |

| Indonesia | 7 |

| Japan | 8 |

| Malaysia | 7 |

| Singapore | 0 |

| Thailand | 14 |

| Vietnam | 24 |

| Other | 10 |

| Net cash & receivables | 7 |

| Rounding | 1 |

100 |

When asked to name the greatest difficulty facing a Prime Minister, the British leader Harold Macmillan apparently never said: "Events, dear boy, events." (He may have wished that he did.) There are some events that one can see coming, but play out over timescales that prove awkward to handle. It may be challenging to foresee how societies will react, and to determine good courses of action. Given our slow progress on thinking about the changes described here, we hope that events do not overtake us.

At end-June, the estimated current-year PE was 10.6, with a net dividend yield after Asian taxes of 4.6%, and price-to-book 1.6. This represents a slight improvement over the quarter, after strong results from some of our least liquid holdings. The welcome growth in portfolio earnings and dividends per-share should not be regarded as representative of broader market conditions, and nor will the rate of growth be sustainable. The valuation seems reasonable, compared to alternatives, given our conservative approach to accounting (recurrent earnings, dilution, etc) and a portfolio which we hope will prove over time to be more resilient than average. However, the risks to business globally, and to the underlying businesses of our portfolio holdings, remain unusually high.

A peaceful summer to all our readers.

Claire Barnes, 10 Jul 2019

| Home | Investment philosophy | Fund performance | Reports & articles | *What's new?* |

| Why Apollo? | Who's Claire Barnes? | Fund structure | Poetry & doggerel | Contacts |