Apollo Asia Fund's NAV fell 23.5% in the first quarter of 2020, to US$1,606.03 (Series A shares), a level last seen in 2012.

|

|

|

|

The quarter turned out to be dominated by the COVID-19 pandemic - but travel disruption started grounding Asian investors right from the start. The New Year opened with massive floods in Jakarta, closing the airport and bringing home the scale of subsidence and sea-level rise which brought urgency to plans for a new capital. Next Manila airport closed, due to an eruption of nearby Taal volcano. It was only from mid-January that stories of the new coronavirus started to circulate widely. Public health precautions were initially taken in stride; a string of virus outbreaks had been deemed serious in Asia and ultimately contained, including SARS, bird flu, swine flu, and MERS. It was lockdown in Wuhan on 23 January that really caught our attention: confining the 11 million residents of such a major city - and just before many were due to travel home for Chinese New Year. The restrictions in China spread fast, restricting the movement of some 50m people by the following day, and 800m by February. Such drastic action seemed unthinkable elsewhere, as other Asian governments took standard precautions, screened travellers, and started isolating and quarantining and contact tracing with varying degrees of efficiency. Rolling cancellations of conferences and meetings played havoc with schedules and travel-dependent businesses, while many of us worried about supplies from China, but by early March the containment exercises seemed to have been effective and there was optimism about a gradual return to normality - until the huge outbreaks in Europe and the US, the unexpectedly chaotic response of western governments, and the second wave of infections in Asia. By 25 March, it was said that 3 billion people were under lockdown. Now, governments are adopting emergency powers with the insouciance of the Sorcerer's Apprentice - and since command economies developed over normal timescales proved not to work too well in the long run, it is hard to imagine the social and economic fallout from this sudden unplanned experiment.

Meanwhile in Malaysia, the elected government of Pakatan Harapan (Coalition of Hope) was overturned in an extraordinary series of political manoeuvres, and a Malay-dominated government sworn in on 1 March by the new king. Reformist ministers and technocrats were swept away, including the medical doctors who had led a measured and reassuring response to the pandemic. The respected Attorney General and head of the anticorruption commission resigned, casting doubt over ongoing trials and investigations. Considered policies were swiftly abandoned, apparently heedless of international opinion: more land is to be converted to oil palm. Meritocracy is out: it has been proposed that leadership of government-linked companies, which dominate too much of the Malaysian economy, should henceforth be granted to government MPs, and that being an MP is qualification enough. Meanwhile, parliament has not been allowed to convene since the crisis, and is currently scheduled to assemble only from 18 May. Nationwide Movement Control Orders came into effect on 18 March and have been repeatedly extended. The hobbling of domestic constitutional procedures is a concern, and the current low level of scrutiny convenient for the perpetrators.

While movement restrictions have been introduced in many countries, sensitivity to suffering, evidence-based decisionmaking, and pragmatic, competent leadership will make a big difference to outcomes. Many Asian governments lack some or all of these characteristics. However, the situation remains better than in the US where the disadvantages of a monetised health system are now clear. The public health response in countries such as Taiwan, South Korea and Singapore has been praised. It will be interesting to see if positive social changes ensue, or new opportunites arise, from the flexibility necessarily adopted everywhere.

I wrote on 23 March about the selloff and valuation; coincidentally that marked a temporary bottom. Markets rallied slightly into the month-end, and the bounce continued into the first half of April. However, given the rapid global spread of the virus, dwindling hopes of imminent herd immunity, and an already-huge impact on livelihoods and balance sheets, timeframes for "normalisation" have extended greatly from those expected when markets were at similar levels a month ago.

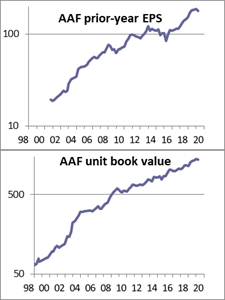

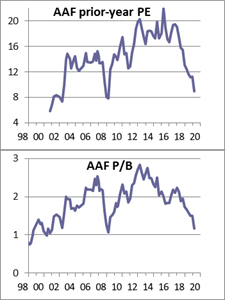

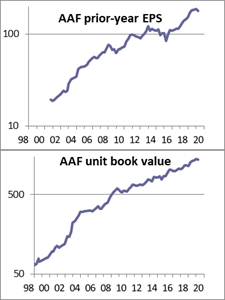

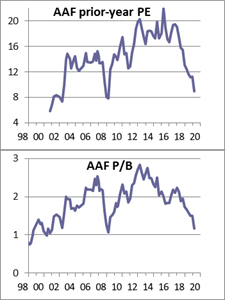

In January I showed you charts which included the underlying earnings and book value for each Investor Share, while noting that the upward march in these (and in dividends) had recently been accompanied by derating. At this stage the current-year estimates would be worthless, so we'll focus on the historic earnings (for the last full financial year to be reported), and the book value per share. The latest results round has not changed the picture very much, so this time we display the progress in both measures on a log scale, which shows that the rate of growth has remained remarkably steady. Over the last 5, 10 and 15 years both historic EPS and historic book value have grown at compound rates of 10% per annum. We were lucky to achieve much higher rates in the first few years of the fund, coming out of the Asian crisis, but at current low interest rates and given our recent risk aversion, 10% is enough to keep us quite happy. For a fundamental investor, these charts are much more revealing than our own NAV performance charts based on the latest market prices of our holdings. The accelerated derating takes us back to valuations at the low end of the range seen over the life of the fund, which suggests an attractive entry point.

Now for the caveats. I confess that the steadiness of these growth rates surprises me, as our companies have seemed increasingly accident-prone in recent times. Looking at each company in the current portfolio, and considering whether it has broadly lived up to our expectations at the time of purchase, yes or no, the results are about 50/50. I did not try this particular exercise in earlier years, and it is very imprecise, but I think in the noughties we had a much higher percentage of successes to duds. So this is disconcerting. It may be that my judgment, or my effectiveness in discovering new investments, has deteriorated. My impression, though, is that the odds have also shifted, with business risks rising, as the years of easy growth and the predictable Asian success of simple business models give way to a much more complex operating environment. Over the last twenty years, conflict has accelerated, global power balances have been shifting, the ideal of a rule-based international order has been breaking down rather than gaining adherents, we've been running ever closer to the limits of resources and eco-services, and the natural world has been biting back. We've written about damage to our holdings from the capricious actions of governments. We also spend an increasing amount of time pondering the adequacy of management teams to face the new challenges. Good operators of their core business may not be sophisticated in financial management, and allocate capital imperfectly, overlook potential risks, or take decisions that enrich their bankers at the expense of the shareholders.¹ Other management teams may rise well to the first crisis, and to the next, but burn out - or just lose their spark, and the energy required to plan well for succession and rejuvenation.²

These are issues with which we've been grappling for several years. They are likely to be exacerbated by the extreme stresses of the COVID-19 outbreak and its aftermath. Unfamiliar situations will heighten the risk of normal human weaknesses: we expect to see more failures of imagination, control, and negotiating skill. If more crises occur, or the pandemic is prolonged, recurrence will test the resilience and endurance of management.

| |

Agility and leadership skills will be important. We don't own any of the AirAsia group companies, but admire the communication skills of its co-founder Tony Fernandes, whose recent message to customers came as a breath of fresh air after a torrent of formulaic assurances in the inbox. Regulators in several countries allowed businesses to delay their annual general meetings; some companies moved with alacrity to postpone interaction with investors. Others stepped up with enhanced briefings - and it was a company in Vietnam, where AGMs are impressive exercises in shareholder democracy, that invited us to our first virtual AGM. FPT's meeting looked good. Sitting in Malaysian lockdown, we didn't have the benefit of sitting next to a Vietnamese translator, so understood very little (fortunately the company had solicited voting in advance on the formal resolutions), but it was an excellent first effort, and the company asked for feedback so we'd guess that translation may well be arranged for next year.

Investors of our era have learned the dangers of the phrase "This time is different". This time, it may be equally dangerous not to acknowledge the differences. We are accustomed to crashes from overexuberance - the bursting of great financial bubbles. We are accustomed to crises in individual markets, or regions, while business-as-usual continues elsewhere and provides havens for the mobile and resources for the return to normality. During such crises, we are accustomed to tortoises regaining ground from headline-hogging hares; this time some (not all) undeserving hares seem to be lucky beneficiaries (at least on the first wave), and some sensible tortoises will be swept away too on the floodtide.

Apart from company performance, there is a risk of further derating. Many market participants had become accustomed to a market uptrend with low volatility, and may now become less inclined to take equity risk, especially cross-border risk. Some will need to raise cash, for all sorts of commonplace reasons. Pension assets will have been reduced by the market declines, and although pension liabilities will also be affected by changing assumptions on longevity, problems are likely. Capital controls and tax increases may be considered again in many countries. (If the movement of people and goods can be so suddenly curtailed, other ideas may no longer be unthinkable.) Populist and authoritarian governments add further uncertainties. Investors may be jumpy, and not every seller will find a willing buyer at the right moment. Liquidating funds may be exposed as forced sellers, contributing to declines. Asset prices may gap down. We're attempting to store real wealth, to preserve or augment purchasing power: there is no guarantee that success will remain normal.

As the inherent risk of equity investment becomes apparent once again, those who have no stomach for volatility may prefer to reconsider their exposure. Others may decide that it's time to invest in (by spending on) relationships, community, or resilience; investments are not always financial. In the short term, bank deposits, treasury bonds, gold or other "safe" assets in countries of origin or residence may provide appropriate havens, especially in nominal terms. (Safety over the long term, and in real terms, is another matter, and should certainly be considered.) However, in the darkest days of the Black Death and other disasters, trade continued, new ventures were undertaken, and the foundations of fortunes were laid. Prosperity has come from human enterprise, rather than from buried hoards. (Those have sometimes provided windfalls for later finders.)

For equity investors, after all this has been said, valuations are greatly improved. The risk of a global health crisis delivered by a virus, fungus, or super-resistant bacteria has been flagged for years. Boosting GDP by environmental destruction to build more empty high-rise buildings for sale to foreigners as financial assets was clearly unsustainable. The growing dominance of illth-creation over wealth creation was problematic. Now there's a chance to reconsider the sort of societies we would like to live in, and the appropriate taxes and incentives to steer in those directions. In any case, while the timing and suddenness of the change were unforecastable, other aspects were entirely predictable, and not previously discounted. Now, at least some of these risks are reflected in prices.

A long-term investor assessing the prospects may now therefore be more confident than before the decline. We wrote this time last year about the arithmetic of expected return, starting with the dividend yield, plus expected growth (depending on opportunities, and the efficiency of capital allocation), which may together be approximated by the earnings yield. We should adjust this mentally, if imprecisely, to allow for costs and Net Negative Surprises. A historic earnings yield of 11%, if taken as a guide to expected profitability after a crisis which passes, clearly gives us a better prospect for long-term returns than the earnings yield of 5-6% typical in some recent years - double - or after costs, more than double. The likelihood of opportunities for spectacularly good investments may also be better in times of crisis, than when the whole field is well picked over: if we can look in the right places when others are distracted, or have cash available when others do not, we might find bargains. Given the number of Negative Surprises in recent years, and the heightened business risks, we would not count on any Positive Surprises - but can hope.

When we started Apollo Asia Fund, in the wake of the Asian financial crisis, we did so because the opportunities seemed compelling. I make no such representations now, but the prospects seem reasonable, and I'm not convinced that other major asset classes look significantly better. The fund will again be open for limited new investment, with preference to existing investors and those who expressed interest in the past. Some investors may wish to redeem instead. I urge you all to consider the issues for yourselves, and trust your own judgment: on the most important issues facing us now, there are no experts; we are all feeling our way. Whatever you decide, I wish you good fortune and good health.³

Claire Barnes, 16 Apr 2020

| Home | Investment philosophy | Fund performance | Reports & articles | *What's new?* |

| Why Apollo? | Who's Claire Barnes? | Fund structure | Poetry & doggerel | Contacts |